Abby Mackey

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

Noah Robbins’ adoption story published one year ago today.

Splashed across the first edition of goodness was then-5-year-old Noah with his blaze-red hair, his adoptive parents’ shining smiles and the Row House Cinemas marquee that read “Happy Adoption Day, Noah.” It was the culmination of a four-year adoption journey for the Lawrenceville couple, 1,275 days in foster care for their son and a year of learning to care for a medically complicated child.

Splashed across the first edition of goodness was then-5-year-old Noah with his blaze-red hair, his adoptive parents’ shining smiles and the Row House Cinemas marquee that read “Happy Adoption Day, Noah.” It was the culmination of a four-year adoption journey for the Lawrenceville couple, 1,275 days in foster care for their son and a year of learning to care for a medically complicated child.

But among all of the formal agreements necessary to welcome Noah into their family, there was also a private one.

“When we first got custody of Noah, we were told he would never walk,” Michaela Robbins, Noah’s adoptive mother, said. “He said to us, ‘I will walk. Find someone who can make me walk. I know I can do it.’ ”

Noah’s aggressive form of arthrogyposis, called Escobar syndrome, caused joint contractures so severe that he “walked” on his knees. He was already “perfect” in the eyes of his new family, but recognizing the goal he’d set for himself, his parents sought to make walking a reality.

The pandemic worked in their favor as they consulted with specialists across several states without leaving their home. From behind a webcam, they eventually connected with one of the country’s most experienced surgeons for this condition from Nemours Children’s Health System in Delaware.

Noah spent six weeks in casts to straighten his bent legs as much as possible ahead of surgery. In May, his surgeon removed 2 inches from the centers of his thigh bones to accommodate his shortened tendons, resulting in far straighter limbs.

“We really thought, OK, this kid will get his cast off. He’ll be able to have a bath. All is good. We’re so grateful,” Mrs. Robbins said.

The Robbinses were told he’d progress through the stages of walking like a toddler: pulling up to stand, scooting, first steps and more. But on the day his casts were removed, about eight weeks after surgery, the physical therapist looked at the family and said, “I think he’s ready.”

‘Get up’

“All right, Noah, get up,” Dave Robbins, Noah’s adoptive dad, remembers the physical therapist saying.

Just hours after Noah’s reconstructed legs saw the light of day, the 6-year-old pushed himself up to a standing position and took a few assisted steps, far ahead of schedule.

“In my head I pictured it,” Mr. Robbins said. “I thought I’d cry like a baby, but I didn’t. I was in such shock.”

Mr. Robbins let those tears out in the coming days, but, in the meantime, Noah already set his sights on the next goal: The night after taking his first steps — on his feet, not his knees — he said, “I want to learn how to dance.”

Amazing Ava

Mr. and Mrs. Robbins are fans of the PG’s goodness section. They appreciate the spirit of the stories told therein.

On July 9, just about two weeks after Noah voiced his desire to dance, Mrs. Robbins read “Meet Ross dancer Amazing Ava, the ballerina on wheels,” the goodness story about 12-year-old Ava Allenberg, who dances from her wheelchair alongside Cynthia’s School of Dance and Music instructor Sam Skobel.

Mrs. Robbins Googled the studio and placed a call to owner Cindy Zurchin, Ph.D., as fast as her fingers could dial. A meet-and-greet was scheduled soon after.

“Our main interest at first wasn’t about how he’d move. It was really about meeting him and learning about him,” Ms. Zurchin said. “As soon as he walked into the studio, we could see his personality is bigger than life. He’s such an energetic cool, cool kid.”

By September, Noah was a private student of Miss Sam’s, just as Ava is.

‘Isn’t that the dream?’

Noah recently upgraded to a “big boy wheelchair,” which his mom describes as a “La-Z-Boy on wheels.”

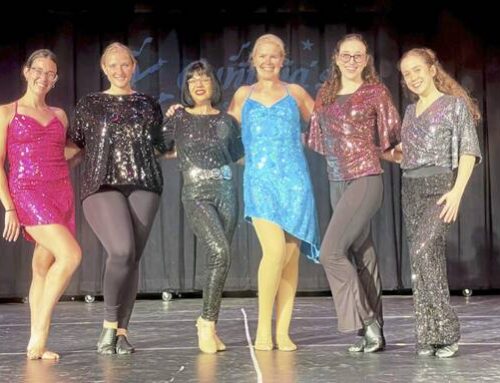

By mid-December, he decked out his black cushy ride featuring “Looney Toons” fenders with gold tinsel, likely to match the gold pants he chooses to wear several days per week. He parked it on the far side of Miss Sam’s studio at Cynthia’s School of Dance and Music in Ross at the beginning of his lesson.

He’ll “always” use a wheelchair for longer distances, but in dance class, he uses a walker to practice his hip-hop routine to the 1976 Rose Royce tune, “Car Wash.”

“I really like it,” Noah said. “It’s hard. It’s hard to remember the dance.”

Miss Sam asks him to pick out three colored circles that she lays on the ground to help him center his footwork. She has three, too, as they perform side by side.

Since the “Amazing Ava” story published, Noah is one of several differently abled students to seek instruction at Cynthia’s school from Miss Sam, who is known for tailoring her teaching style to each of her dancers’ sets of abilities.

“Isn’t that the dream?” Miss Sam asked with tears welling in her eyes. “Isn’t the ideal world inclusion and everyone getting to dance? Isn’t that perfect?”

The next act

As Noah finished his lesson, Ava waited for hers, a scheduling happenstance that crosses the families paths even further.

In a hot pink leotard, nude tights, soft pink ballet slippers and a flawless ballerina’s bun, the girl gave a wide smile when referred to as “Ava, the dancer,” a reaction made more meaningful by her communication challenges.

After wheeling her into the studio, Miss Sam assessed Ava’s muscle tension— one of her biggest mobility issues — as, hand in hand, they carried their arms through the air like any ballerinas would.

That original connection with Ava and Miss Sam inspired Ms. Zurchin, whose doctorate is in education, to write a book about dancers with different abilities called “Ava’s First Dance Recital.” A handful of publishers shot it down, but one company is interested, with more information coming in 2022.

“At the recital, kids came up and said, ‘How’s she going to dance? She’s in a wheelchair,’” Ms. Zurchin said. “They need to be able to read a kids book that says this is dancing.”

Next up might be a book about how a boy with a tracheostomy tube can sing because Noah will likely start voice lessons at Cynthia’s by summertime.

“In some ways it’s surprising, but in other ways, it’s not because he’s always been a performer,” Mr. Robbins said. “Even the very first time we met him, it was like a little performance.”

At home, Noah strives to climb up stairs and onto beds, small steps his parents and physical therapists support, knowing they’re all leaps toward future independence. But those strides are impossible without confidence, which is something his dance studio targets by placing no boundaries on the word “dancer.”

“The show goes on no matter what. It’s the show of life,” Ms. Zurchin said. “With these families, success is seeing them take that next step, that they could extend their arms, could hear that music, to stay with the rest of the group.

“Even if their feet aren’t moving exactly the same, it’s just reaching for more.”

Abby Mackey: [email protected]